DRANGSONG MANUSCRIPTS

|

1. Text number |

Drangsong 134 |

|

2. Text title (where present) in Tibetan |

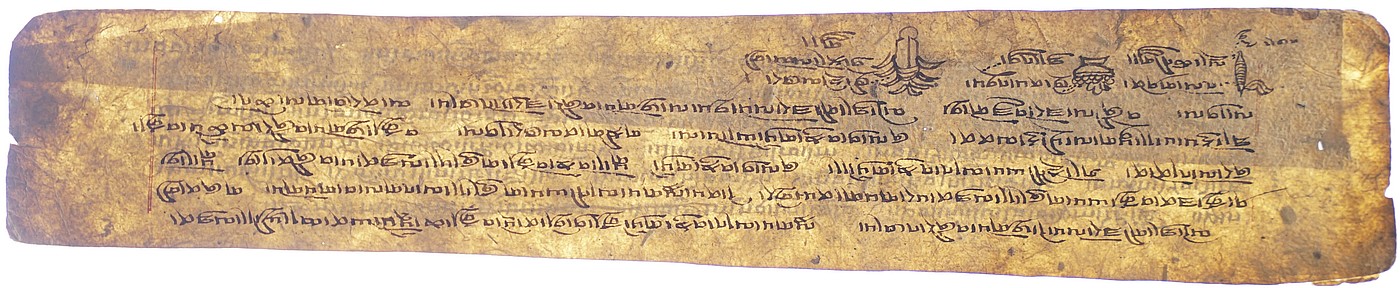

༄༅།།ཀོང་ཙེའི[ཙེས]གནང་བའི་ལྕགས་མདའ་བཅུ་གསུམ་བཞུགས་སོ།། |

|

3. Text title (where present) in Wylie transliteration |

Kong tse’i [tses]gnang ba’i lcags mda’ bcu gsum bzhugs so// |

|

4. A brief summary of the item’s contents |

A ritual of purification through the blood of birds |

|

5. Number of folios |

7 |

|

6. Scribe’s name |

None |

|

7. Translation of title |

Thirteen iron arrows given by Kong tse

|

|

8. Transcription of colophon |

dKa’ ba’i mdos des ’dir phebs shig/ shu bhyo/ ’di skad zhig ni gdan sa chen dpal ldan ri zhing gyi dgon pa’i lho gling ru mgyogs par bzhengs so/ |

|

9. Translation of colophon |

|

|

10. General remarks |

dPal ldan ri zhing dgon monastery was founded in the 11th century by Zhu yas legs po (11th century), and subsequently became one of the five main family monasteries in Central Tibet. The Drangsong collection contains another version of this text (Ds 072). |

|

11. Remarks on script |

dpe tshugs |

|

12. Format |

Loose leaves |

|

13. Size |

7.5 × 34.8 cm 9.1 × 33.4 cm |

|

14. Layout |

|

|

15. Illustrations and decorations |

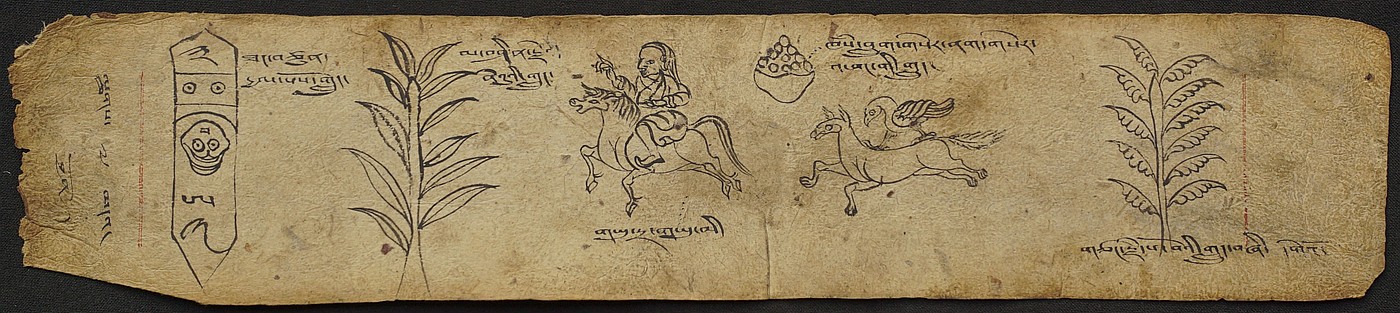

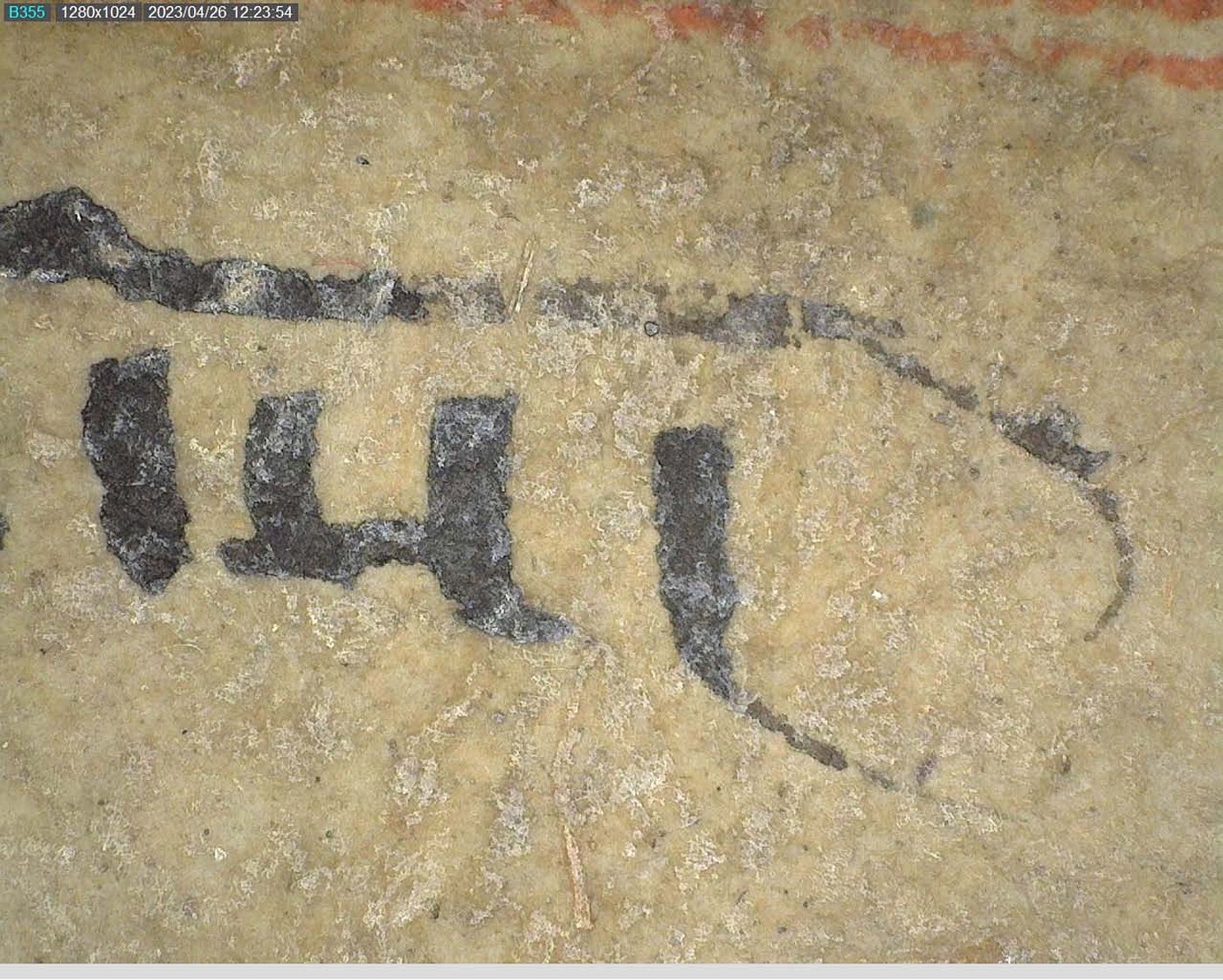

These two folios on the verso of the last two pages of the manuscript are drawn with a total of nine drawings, all but one identified by captions. Below the text of the first folio, we observe, arranged in a row and drawn with small dimensions: a spindle, a container filled with grain, and some sort of vegetal(?). On the second folio, we observe drawn next to each other with greater dimensions: a wooden tablet of a type sometime called shing ri,[1] here inscribed with the number 3 at its top and its base and with two circles in a row (possibly representing a dice), a skull, and the seed syllable a in its main section; a triple-curved plant with linear leaves; a man mounted on a horse; a skull-cup apparently filled with grains; a bird standing on the back of a four-legged mammal, possibly a dog; and a straight plant with lobed leaves. With the exception of the bird on the dog-like mammal, all these drawings are accompanied with very corrupted captions. Three of these inscriptions identify the objects themselves: “the spindle(?)”,[2] “the grains of a millet porridge(?)”[3], “the turquoise horse and the turquoise man”.[4] By contrast, all other inscriptions appear to refer to the objects through their uses as ransoms in obscure charter stories, the names of some figures of which can be corrected from different versions of the Catalogue of the ancient principalities found in the Old Tibetan manuscripts PT 1060, PT 1067, PT 1285, PT 1286, PT 1290, and ITJ 0734, where they also appear[5]: “the ransom of lJang tsha, the gShen [priest of]’Ol”,[6] with reference to the spindle; “the ransom of Khri rje mKhar bu stong lom(?)”,[7] with reference to the unidentified vegetal; “the ransom of King Myang tsun (thang ’tsun)”,[8] with reference to the wooden tablet; “the ransom of Ne’u, Lord of mChims (ma bshin rje≠)”,[9] with reference to the plant ending the upper row; and “the ransom of the golden spindle of dark gold …(?)”,[10] with reference to the skull-cup. The last inscription, written next to the plant ending the lower row, may apply to other drawings as well since it identifies “the four ransoms of Phwa (so ba), Lord of rTsang (gtsang rje)”. It concludes this list by wishing for virtue to be generated from the making of such ransoms.[11] These references are of peculiar interest for Tibetan philology. The Old Tibetan Catalogue of the ancient principalities essentially enumerates the countries, forts, rulers, and ministers of Tibet prior to the rise of the sPu rgyal dynasty. Among the Old Tibetan manuscripts incorporating it, PT 1285[12] and ITJ 0734[13] are healing rituals. They both recast King Myang tsun, Ne’u, Lord of mChims, and Phwa, Lord of rTsang, along with mKhar ba, Lord of dByes (possibly corrupted in our text as Khri rje mKhar bu), as patients, and introduce lJang tsha, the gShen priest of ’Ol, as a healer to the Lord of ’Ol, Zin brang. PT 1285 summarizes poison healing stories, and ITJ 0734 soul retrieval stories. These stories, however, generally do not provide sufficient information on the associated rituals to help us identify the objects drawn on the present manuscript. The only exception is the ransoming story of Phwa, Lord of rTsang, in ITJ 034, translated as follows by Thomas: In the Rtsaṅ-śul country Mtho…was a king, Rtsaṅ-king, Pva-ha. A fiend, Rtsaṅ-fiend, Po-da said: “To a country of fire not hot, water not wet, [I] will carry [you]”. The Rtsaṅ-king Phva-ha summoned the Rtsaṅ [g]śen Sñal-nag; Turnip ‘One-filling’ and Turquoise Slag-cen and bse Pyaṅ-paṅ Pa-myig having been put in fealty to the god, put in fealty to the Rtsaṅ god Pu-dar, and mtshe-mo Number-one and Turnip ‘Good-filling’ and zer-mo Ḥp(h)an-bzaṅs and Mon sheep Ḥbras…wool, a small bre, having been cast as scapegoat for the [king’s] body, the fiend, Rtsaṅ-fiend, Pod-de came accepting: the man went free, the Rtsaṅ-king Pva-va went free.[14] Crucially, this story recalls the drawing of a vegetal and the mention of several ransom items in the associated caption of the present manuscript. It suggests that longer versions of the other healing stories were circulated, in which the ransom items used for retrieving the souls of the patients would have been clearly specified. The relation of these drawings to the main text remains to be properly understood. Only a very short reference is made to “the turquoise horse and the turquoise man, etc.” in the short text in dbu med appended to the main text, in the middle of a series of concepts and objects including the five jewel-colours of the sky, the twelve years, the eight trigrams, the nine astrological charts (rme pa dgu), the arrow and the spindle of variegated colours (’da’ phra ’phang phra), the wooden tablets of the man and woman (pho dong mo dong), etc. that need to be offered as part of a gto (lto) ritual. Similar drawings and captions appear at the end of the manuscript Ds 072, which is concerned with the same ritual. [1] For its other names, see the description of the drawing slipped in manuscript Ds 006. [2] The caption reads: ’phang 2 bya. [3] The caption reads: khre nas ’bras thud ’bru. [4] The caption reads: g.yu rta g.yu mi. [5] For references on the Catalogue, see Uray, ‘The Old Tibetan sources of the history of Central Asia up to 751 A.D.: A survey’, n. 69. [6] The caption reads: ’ol gshen ljang tsha’i glud. Compare especially to the phrases ’ol gshen ’jang tsa mon yug in PT 1285 (r177) and ljang tsa gshen in ITJ 0734 (8r333). [7] The caption reads: khri rje mkhar bu stong lom gyi glud. Compare especially to the phrases dbyes rje mkhar pa in PT 1285 and dbye rje khar ba in ITJ 0734 and to the phrases stong lom ma tse in PT 1286 (07) and stong lam rma rtse in PT 1290 (v5). [8] The caption reads: thang ’tsun rgyal pos glud. Compare to the phrases rje myang tsun rgyal po in ITJ 0734 (8r341), rje myang tsun gyi rgya po in PT 1060 (87), myang chun rgyal po in PT 1285 (r20), and rje myang tsun slang rgyal in PT 1286 (18). [9] The caption reads: ma bshin rje≠ ne’u’i glud. Compare to the phrases rje mchIms rje ne’u in PT 1060 (81), rje mchims rje ’I ne ’u in PT 1286 (20), rje mchims rje ne ’u in ITJ 0734 (8r338), and mchims rje gnyI zla tshe’u in PT 1285 (r92). [10] The caption reads: khaṃs blug gser nag gser ’phang gi glud. [11] The caption reads: gtsang rje so ba’i glud bzhi dge’o /. Compare to the phrases rje rtsang rje’i phyva’ in PT 1060 (74), rtsang rje pva ’a in ITJ 0734 (7r298), and rtsang rje phva and rtsang rje pho bla in PT 1285 (r186 and r184). [12] On this manuscript, see Lalou, Fiefs, Poisons et Guérisseurs. [13] On this manuscript, see Thomas, Ancient Folk-Literature from North-Eastern Tibet, 52–102. [14] Thomas, 92–93. |

|

16. Paper type |

Woven, 2 layers |

|

17. Paper thickness |

0.15–0.17 mm |

|

18. Nos of folio sampled |

f. 7 |

|

19. Fibre analysis |

|

|

20. AMS 14C dating |

|

|

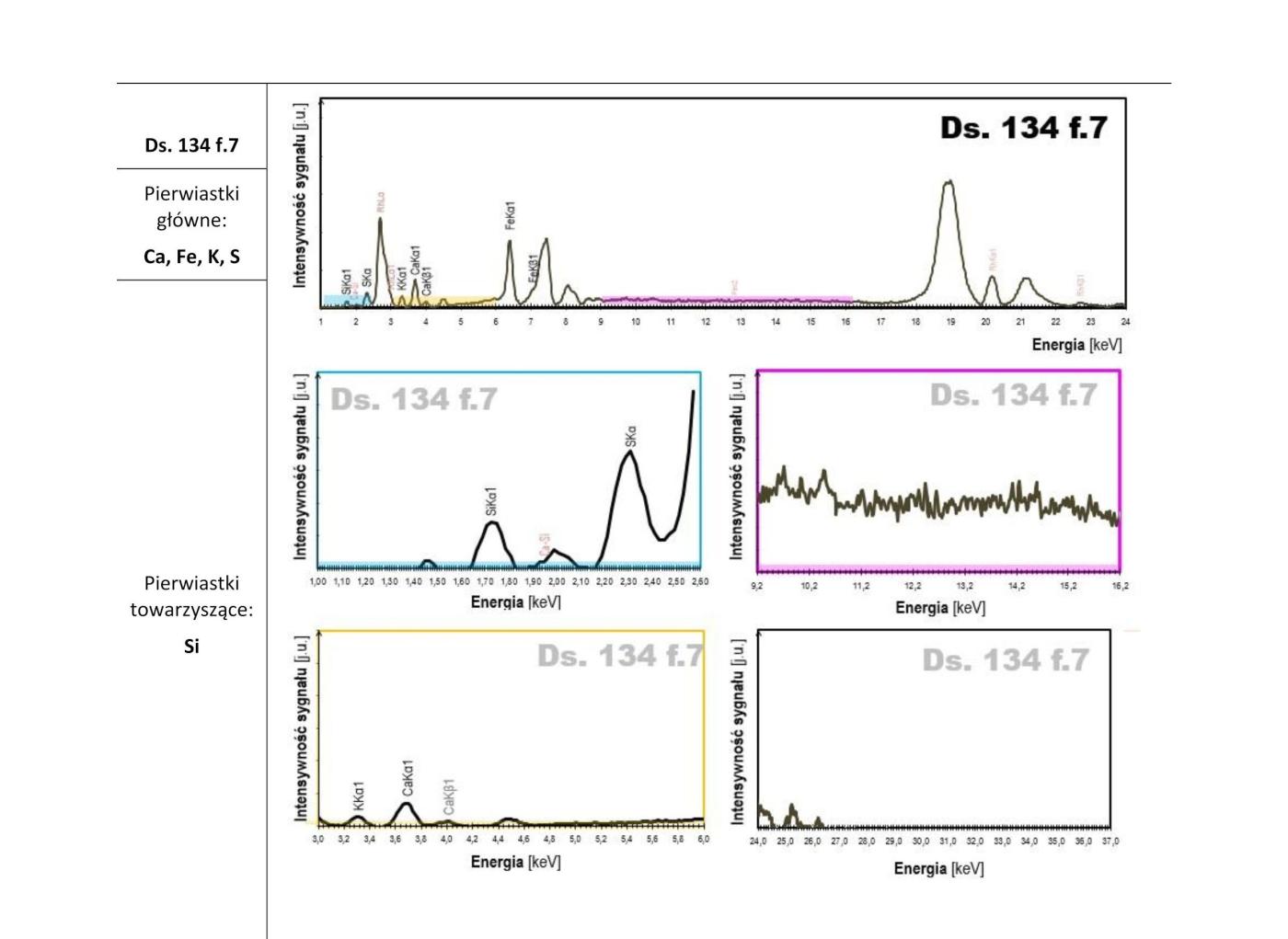

21. XRF analysis |

Main elements: Ca, Fe, K, S, Si Trace elements: Ti, Zn |

|

22. RTI |

|

|

23. GCMS |